The Voyage of Sorcerer II traces an expedition to unlock the genetic mysteries of the ocean

This article was published more than 6 months ago. Some information may no longer be current.

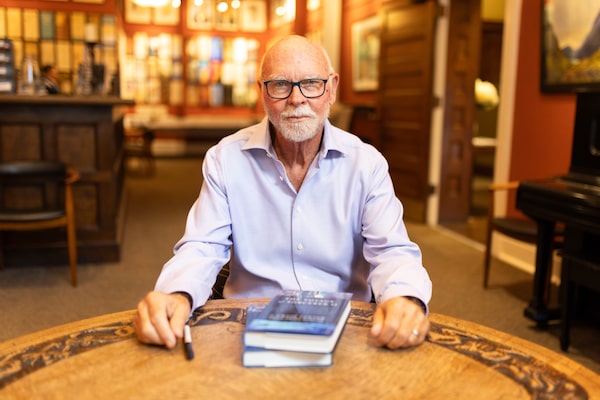

Scientist and author J. Craig Venter signs copies of his new book Sorcerer II: The Expedition That Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome at the Arts and Letters club in Toronto, on Oct. 26, 2023. Melissa Tait/The Globe and Mail

The expedition to crack open the ocean’s genetic treasure chest began in Halifax harbour under an overcast sky.

It was Aug. 20, 2003. J. Craig Venter, the geneticist turned entrepreneur, had arrived with the captain and crew of Sorcerer II, his 95-foot sailing yacht that doubled as a floating field laboratory. His mission: circumnavigate the globe while sampling the ocean waters along the way. It was to be a planet-wide DNA test that would shed light on the full breadth of the ocean’s genetic diversity in a way that had never been attempted before.

Venter was not a novice – to sailing or to mounting large and transformational science projects aimed at overturning the conventional wisdom of his peers.

“Everyone thinks that new discoveries are about making breakthroughs,” Venter told an audience during a recent visit to Toronto, where he sits on the science and innovation advisory committee for the Hospital for Sick Children. But often, discoveries simply overcome bad ideas of the past, he added.

Now 77, Venter was 56 and newly unemployed when he decided to travel around the world by sailboat. By then he was already a world renowned scientist and a notorious iconoclast. His innovative approach to genetic sequencing in the 1990s had allowed him to race the massive Human Genome Project mounted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The effort reached its culmination in the summer of 2000 with the unveiling of a first draft of the full human genetic code three years ahead of schedule by the NIH and Celera Genomics, the company Venter co-founded in 1998.

The joint reveal, brokered by the White House, kept the focus on the future benefits of the achievement for humanity, but Venter has never been shy about saying he won the race. Eighteen months later he was fired from Celera because the leadership of the firm’s parent company “decided they didn’t need this radical scientist any more,” he said in an interview with The Globe and Mail.

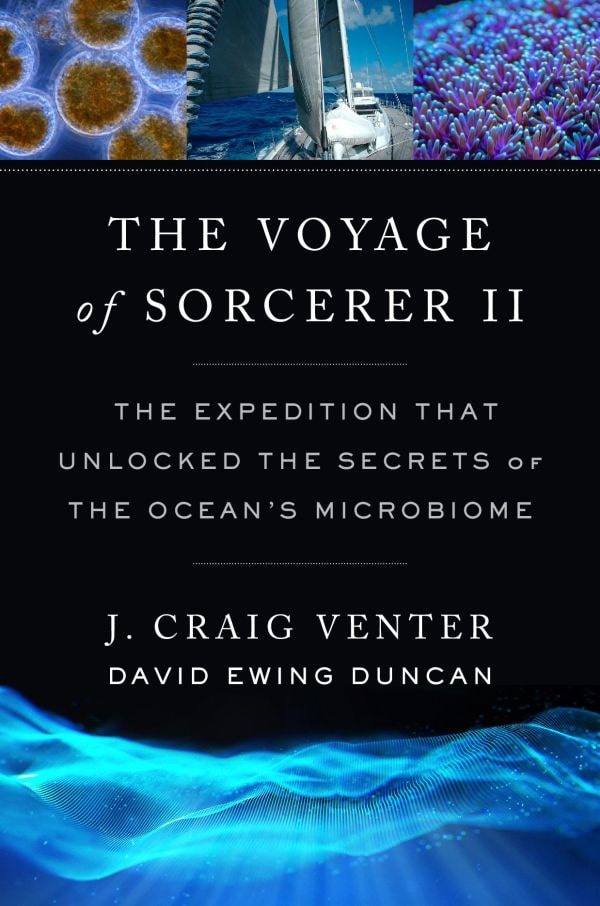

What followed is documented in The Voyage of Sorcerer II, a book by Venter and his co-author, science writer David Ewing Duncan, that provides a personal account of a unique expedition.

For Venter it was to be the ultimate midlife reset – not to mention a chance to irk colleagues in academia and government who were locked into a more conventional approach.

It was “my best idea,” he said. “I found a way to sail around the world on my own boat and do science and get paid for it.”

It was also Venter’s golden opportunity to finally pursue science in a way that most excited him, as it was once done by Charles Darwin and other 19th-century pioneers: by looking and seeing what’s out there without any idea what might turn up.

Even the choice of Halifax as the expedition’s official starting was a kind of homage to this idea. Halifax had also been visited by HMS Challenger in 1873, the first expedition to survey life in the global ocean’s depths.

That historic voyage famously showed that the seafloor was not a biological desert sterilized by extreme conditions, as some thought at the time. No matter how deep, the ocean was occupied.

Venter frames his own voyage in similar terms, as showing that microbial life in the ocean is far more diverse at the genetic level than expected.

His first run at the idea came with a sailing trip in the spring of 2003 to sample waters in the Sargasso Sea, a portion of the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida where drifting micro-organisms are partly confined by currents.

A small team including expedition scientist Jeff Hoffman filtered some 400 litres of seawater to capture bacteria and then froze the contents for detailed analysis on land.

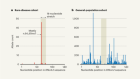

The results were obtained using the same “shotgun sequencing” technique that Venter had applied so successfully to the human genome. It starts with pulverizing DNA into short random strands that can be read by sequencing machines and then using a computer algorithm to match overlapping readouts from the fragments to reconstruct a complete genetic sequence.

But now, instead assembling the code of a single organism, the algorithm might be working with DNA from many separate bacterial species, invisible and indistinguishable from one another except through their genetic fingerprints.

The result “blew our minds,” said Venter. The Sargasso Sea was teeming with diversity. As detailed in a research paper based on the analysis, the team found 1.2 million newly reported genes from at least 1,800 species including bacterial groups previously unknown to science.

It was an impressive haul but Venter was already working on a far more ambitious sailing trip to gather samples from around the world and show not only the vast richness of microscopic life in the seas but its variation from one location to the next. The uniform blue expanse that represents the ocean on a world map might, in reality, be subdivided into countless microbial domains, evidence of the dynamic multibillion-year evolutionary history of life on Earth.

By summer the expedition was coming together, drawing skepticism from some but also winning early support from some powerful allies, including Ari Patrinos, who was then director of biological research at the U.S. Department of Energy and key funder. Another supporter was the late E.O. Wilson, the celebrated Harvard University biologist.

“He liked that I was asking global questions and treating it as a much big picture,” Venter said.

The expedition’s first sample was collected in Halifax Harbour followed by a road trip by Venter, Hoffman and others across the width of Nova Scotia to scoop water out of the Bay of Fundy with the help of a local fisherman. The drive included a visit with Victor McKusick, the Johns Hopkins University professor known as the father of medical genetics, who had a summer home in the area.

The Sorcerer II soon headed back down the Atlantic coast, first to Hyannis, Mass., and then Annapolis, Md., for a final series of preparations that would allow the ship, under the guidance of Canadian-born Captain Charlie Howard, to travel the open ocean for months-long stretches without support.

In December the sailing and the sampling continued, with the ship making its way to Florida and on to the Caribbean and the Panama Canal. Venter’s initial plan had been to sail around South America but the time of year combined with the treacherous currents around Cape Horn ruled out a long journey around the continent. And there was the likelihood that Brazil would not permit sampling in its territorial waters – a harbinger of the growing debate over who holds sovereignty over genetics information obtained from the environment and any future profits that such information may generate. Although the expedition’s findings were always intended to be made public domain, Venter had already been branded “bio-pirate of the year” by one environmental group ahead of the voyage.

Sorcerer II entered the Pacific via the Panama Canal and onto the Galapagos Islands, following in Darwin’s footsteps but with the added complication of negotiations over permits and transport of samples back to the United States. The joy of exploring the biological wonderland shines through in Venter’s account, as he and his colleagues search for unique environments to sample, including a hydrothermal vent off Roca Redonda, a tiny steep-sided island that is the eroded remnant of an underwater volcano.

From the Galapagos the crew travelled west across the South Pacific, sampling the waters roughly every 200 miles.

“That’s roughly how far you can sail in 24 hours in a decent-size sailboat,” Venter said. “And so we’d stop once a day and take a sample.”

What the scientists on Sorcerer II found was that, at each stop, more than 80 per cent of the genetic sequences was “totally new and unique,” Venter added. The ocean was, as he had guessed, a far more complicated and genetically diverse patchwork of microscopic ecosystems than had once been supposed.

Other adventures were to follow, including an encounter with a SWAT team in Brisbane, which had been called to investigate whether the ship was a floating meth lab – apparently the work of a jilted fiancé whose former partner had become romantically involved with one of the crew. Later, some of the tensest moments of the voyage came during a stop at the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean where the crew had their passports seized by the British military, who threatened to impound the Sorcerer II until Venter was able to reach the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom by satellite phone.

The circumnavigation was completed in January, 2006, when the ship reached Palm Beach, Fla., nearly two and half years after departing Halifax. But it was only to be the beginning of a more sustained campaign of ocean sampling that would next take the ship up the Pacific Coast to Alaska and then on a trip through European waters from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Further excursions to Antarctica and the North Atlantic followed as the sampling work continued until 2018.

The final section of the book details the research results that have issued from the work, including insights into the active role that viruses play as managers of the marine ecosystem with implications for how nutrients cycle through the oceans.

The most significant impact of Sorcerer II’s voyage may be that it signalled the coming of age of metagenomics, the now widely employed technique of sampling the environment rather than organisms directly to understand the biology of the planet. It is an approach that has seen the merge of a revolution in genetics with big data and computational tools.

Despite Venter’s reputation as a pioneer in the use of algorithms to advance genomics, he takes a measured view of the role that AI will play in biology’s next chapter. Algorithms are tools that are only as good as the data they are trained on, he said. Ultimately it’s the mind of the scientist, and the spirit of discovery that gives direction and meaning to the scientific process.

For all its power, he added, AI “can’t answer questions about the unknown.”

Report an editorial error

Report a technical issue

Editorial code of conduct

Follow related authors and topics

- Ivan Semeniuk

Authors and topics you follow will be added to your personal news feed in Following .

Interact with The Globe

- MarketPlace

- Digital Archives

- Order A Copy

Boat Focus: Sorcerer II

E xplorations of the globe under sail, like Darwin’s voyage aboard the ship Beagle and the voyage of the Royal Navy ship Challenger in the 1870s, were scientific milestones that greatly increased our knowledge of the planet. For biological scientist and lifelong sailor Dr. J. Craig Venter those passages provided a major inspiration for his extensive voyaging aboard his 95-foot sloop Sorcerer II . On two separate expeditions Venter, along with a group of fellow scientists and Sorcerer II ’s crew, gathered biological samples from the world’s oceans. Sorcerer II sailed more than 65,000 miles and harvested a vast biological trove that is being used to expand knowledge of the world’s biological organisms.

In the 1990s, Venter and his team successfully sequenced the human genome in parallel with a government-funded effort. Venter also founded the biotech firms Celera Genomics, the Institute for Genomic Research and the J. Craig Venter Institute.

During a recent phone call Venter said that when he was serving in the Navy during the Vietnam War and stationed at a Navy facility in Da Nang, he often thought about sailing. “The idea of the sailing around the world helped keep me sane,” Venter said. When deciding to launch his first worldwide sampling expedition he realized he could combine his desire to do a circumnavigation with science. “A chance to do that and do my research at the same time was a phenomenal opportunity.” Venter and David Ewing Duncan have written a new book about the sampling expeditions called The Voyage of Sorcerer II published in September by Harvard University Press.

Venter and crew collected samples every 200 miles by pumping 200 to 400 liters of seawater aboard and running it through a series of increasingly smaller filters designed to capture ever smaller denizens of the aquatic world. The filters with their specimens were then frozen on board and when Sorcerer II arrived at a port that had air freight service the frozen filters were airlifted back to Venter’s lab for analysis. The amount of data acquired was staggering. “We discovered more species on these voyages,” Venter said, “than the entire history of scientific discovery put together.”

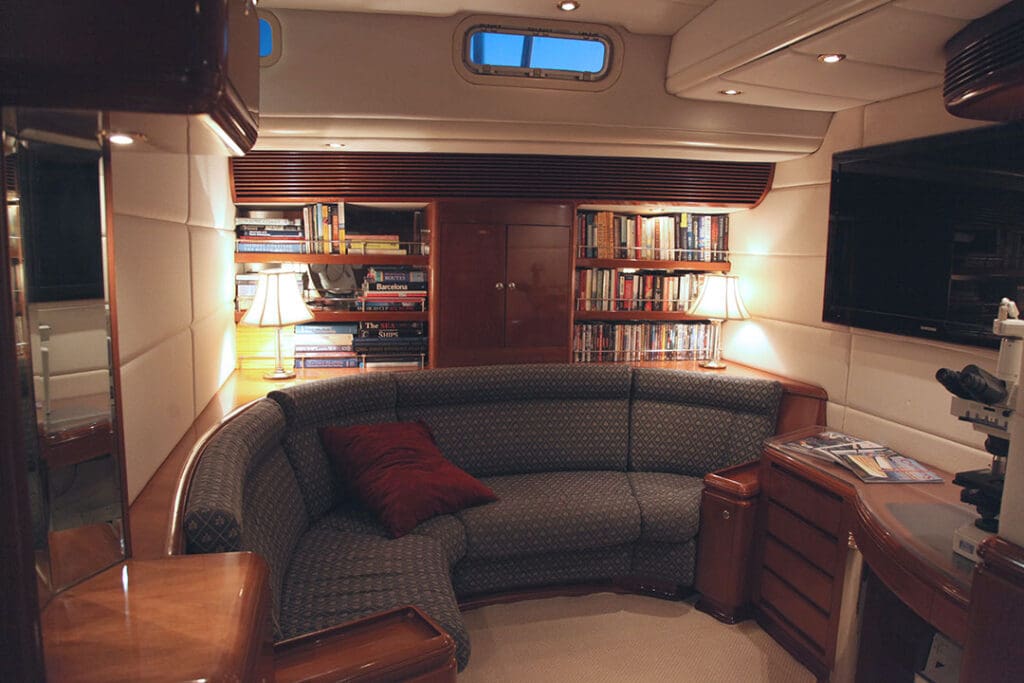

During Venter’s research voyages, the boat — currently under different ownership, Venter sold it in 2019 — was equipped with a 300 horsepower 6CTA8 3M Cummins diesel with an adjustable pitch Max Prop propeller and fuel tankage of 2,324 gallons and water tankage of 634 gallons. Its fin keel has a draft of 10.2 feet. Even though a large boat Sorcerer II has manual cable steering. It was also equipped with bow and stern thrusters, water maker, two gensets and a host of other gear for crew comfort while conducting its research worldwide.

The tough hull of e-glass and Kevlar was well suited to the demands of many ocean miles. An excerpt from the Venter and Duncan’s book provides a glimpse of how Sorcerer II ’s captain viewed the vessel. “Sorcerer is not too big and not too small,” said Captain Charlie Howard, describing his vessel…. “She is smart and well put together with the best components and a lot of thought and engineering. She has long legs and once took us almost six thousand miles on one load of fuel from Cape Town to Antigua. She thrives on lots of attention and when you don’t give her the attention, she gives you surprises. She is a good friend when the going is rough, and she has never let me down.” n

- Featured News

- Artificial Intelligence

- Bioprocessing

- Drug Discovery

- Genome Editing

- Infectious Diseases

- Translational Medicine

- Browse Issues

- Learning Labs

- eBooks/Perspectives

- GEN Biotechnology

- Re:Gen Open

- New Products

- Conference Calendar

- Get GEN Magazine

- Get GEN eNewsletters

From Sequencing to Sailing: Three Decades of Adventure with Craig Venter

In a plenary public appearance at the Molecular and Precision Med TRI-CON event in San Diego, a relaxed Venter reflected on his career highlights, controversies and future priorities for genomic medicine

By Fay Lin, PhD

J. Craig Venter, interviewed in the plenary session of Molecular and Precision Med TRI-CON on March 6, 2023, in San Diego. [Cambridge Healthtech Institute]

SAN DIEGO— More than two decades after making history by being an integral part of the Human Genome Project celebration, J. Craig Venter, PhD still holds a few surprises up his sleeve. In a public appearance at the annual Molecular and Precision Med TRI-CON event, he revealed how he nearly pulled out of the White House celebration in June 2000 after objecting to a first draft of British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s prepared remarks.

The TRI-CON event, hosted by Cambridge Healthtech Institute, celebrates its 30th year this year.

“[The genome revolution] has fallen way short. The sequencing technology has improved by so many exponents but people think that the sequencing is sufficient,” said Venter. “I learned through my assumptions made on my own genome that without measuring the comprehensive phenotype, the genome was virtually worthless.”

Venter emphasized that studying human biology in conjunction with the genome is required to make strides in genomic medicine. “If I had to choose between having my genome sequence and a whole body MRI for health,” Venter said, “I would take the whole body MRI. But the future is combining the two.” Venter co-founded Human Longevity, a company offering state-of-the-art personal genome and imaging screens for clients, in 2013.

Venter’s legacy as a genomics legend established its roots over 30 years ago, starting with a paper published in Science in 1991 , in which Venter’s team at the National Institutes of Health applied random cDNA sequencing to identify more than 300 human genes of plausible biological function, coining the term “expressed sequence tags.”

“My institute director of neurology complained that I was wiping out all these PhD theses randomly by publishing all these sequences. Of course, that wasn’t the goal. The point was that I’d spent 10 years trying to get one gene and I didn’t want to have to do that again.”

Throughout the 1990s, Venter’s notoriety steadily grew with controversy over the commercialization of DNA discoveries. In 1995, Venter’s team at his non-profit, The Institute for Genome Research (TIGR), published the first microbial genome sequences. In May 1998, he stunned the public HGP consortium by announcing a for-profit effort to sequence the human genome, which later became Celera Genomics.

Venter remembered the day at the White House, June 26, 2000 , when President Bill Clinton celebrated the completion of the first draft of the human genome alongside National Human Genome Research Institute director, Francis Collins MD, PhD. The event was the culmination of a diplomatically negotiated truce of sorts.

The White House ceremony “was dictated by when Celera finished the first assembly in its computer. That’s when we actually had the first genome. There was a lot of back and forth politics because the public effort hadn’t finished their assembly yet,” Venter said.

Venter recalled reviewing British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s speech the night before the ceremony and nearly withdrew from the White House event. “[Blair’s speech] was totally lopsided, attacking Celera and companies sequencing genomes. I said, ‘If you want me to show up, you’ll change the speech.’ [After a back and forth] the White House science advisor called me at 1 am and assured me that the speech had changed.”

Venter’s decision to agree to a joint declaration was “a moment of pragmatism” that actually angered his team and wife, whom Venter says did not speak to him for a week.

“The reality was that Celera was so far ahead and people just wanted to announce and publish it. I thought it wouldn’t help science at all if we undercut the NIH and decided that the best thing for science and the public was to have a truce,” stated Venter.

The personal genome

Since the White House announcement in 2000, the field of genomics has continued to boom, most recently culminating with the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) Consortium’s sequencing of the entire human genome in 2022. Asked for his thoughts on these advances, Venter was unfazed.

“We ‘finally finished’ [the human genome] so many times that I lost track! It’s never finally finished, as each of us has a completely unique genome sequence.”

Venter emphasized how each individual’s diploid genome presents orders-of-magnitude more variation than the haploid representation, noting how Sam Levy PhD and colleagues from the J. Craig Venter Institute published the first relatively complete diploid genome — Venter’s personal genome—in 2007.

When asked about the value of genome data to the personal owner of the genome, Venter reflected on his own experiences sharing his genomic information with the public.“My sequence has been out there for so long. There were many people publishing papers of new childhood diseases that I should have died from!” said Venter.

Venter stated that genomic information should be personally controlled, where individuals make the decision on whether to make it publicly available the same way that he did. In addition, Venter said his decision to share his genome was in response to the fear of genome sequencing at the time.

“You might recall editorials [stating] how dangerous it was to have your genome sequenced. Donating my genome and making it available was meant to prove that it wasn’t something to fear,” said Venter.

Under the sea

Venter closed the interview by describing the expansion of his work into metagenomics and his new endeavors sailing the world, a vision that Venter said “kept him sane” during his time as a medical corpsman in Vietnam.

“Once we [sequenced the first genome], we got tons of funding to sequence every genome on the planet,” said Venter. “We did what the Challenger expedition did in the 1870s, where we sailed around the world to examine the bottom of the ocean,” Venter continued.

Venter described shotgun sequencing of filtered sea water samples and being “blown away” by [the diversity of organisms]. He published this sequencing work from the Sargasso Sea in Science in 2004. Venter painted the voyage as a mix of scientific discoveries, logistical challenges and near catastrophe.

“Darwin had it easy!” Venter said. “He could collect samples from anywhere. Nowadays, we need a permit from everywhere to take a water sample 200 miles off their coast. We got arrested by the French and British government. The French even threatened to sink our boat! There was a lot of excitement just to sequence these new genomes.”

Venter has documented these nautical adventures in his upcoming book, co-authored with David Ewing Duncan, called The Voyage of Sorcerer II: The Expedition that Unlocked the Secret’s of the Ocean’s Microbiome . It will be released in September 2023.

OncoMethylome Enhances Pharmacogenomic Services in Deal with BioTrove

Mechanism for gene silencing in skin cancer discovered.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- The Big Story

- Newsletters

- Steven Levy's Plaintext Column

- WIRED Classics from the Archive

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Buy Craig Venter's Ultra-Luxurious Lab Yacht Today!

Current owner J. Craig Venter, wealthy maverick geneticist

Sail the world's oceans in style — and revolutionize genomics! Three well-appointed cabins sleep up to eight. Galley features Corian countertops and is stocked for gourmet cooking. Enough scientific equipment on board to sample every microbe in the sea. You might hit the doldrums, but you'll never be overbored: An A/V network lets any of five flatscreen monitors display output from radar, DirecTV, DVD, navigational computer, laptop, or microscope. You can't afford not to buy this boat.

Type Sailing sloop Year 1998 Top speed 10.5 knots Plush rating Bentley Engine 300-hp diesel (What were you expecting, a transgenic whale heart?) Hull materials Balsa and PVC foam with laminates of unidirectional E glass and Kevlar, bonded with epoxy resin at 113 to 122 degrees. (Kraken-proof.)

Accomodations • King-size master stateroom; two cabins, each with two twin beds and private heads. • Separate crew quarters, galley, aft dive cockpit, and salon/office.

Hardware • DirecTV and two 200-gig servers of networked music. Bose speaker system. • Hall Research Technologies matrix to control the video array.

Research gear • Tube that sucks ocean water through three filters, each capturing smaller microbes. • Freezer to preserve and store microorganisms. • Nikon Eclipse 6600 fluorescence microscope that can see into a bacterium's soul. (Bonus: Name any newly discovered microbial species after that sauced model you're bound to pick up in Ibiza. Think Bacillus gisellensis .)

Price $5.25 million (some scientific equipment not included)

Start Previous: Atlas: Airport Delays Are Getting Worse, So Pack Your Patience Next: Jargon Watch: GPS Shield, QUID, Prehab

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOK REVIEW

- 18 September 2023

Geneticist J. Craig Venter: ‘I consider retirement tantamount to death’

- Heidi Ledford

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

The Voyage of Sorcerer II: The Expedition That Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome J. Craig Venter & David Ewing Duncan Belknap Press (2023)

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 621 , 465-466 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02907-9

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Microbiology

- DNA sequencing

‘Poo milkshake’ boosts the microbiome of c-section babies

News 24 OCT 24

Animal-to-human viral leap sparked deadly Marburg outbreak

Anti-viral defence by an mRNA ADP-ribosyltransferase that blocks translation

Article 23 OCT 24

‘Phenomenal’ tool sequences DNA and tracks proteins — without cracking cells open

News 10 OCT 24

Are you what you eat? Biggest-ever catalogue of food microbes finds out

News 29 AUG 24

Rare developmental disorder caused by variants in a small RNA gene

News & Views 12 AUG 24

Brain stimulation at home helps to treat depression

News 21 OCT 24

Smart insulin switches itself off in response to low blood sugar

News & Views 16 OCT 24

Assistant Professor of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology

The Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine (http://mgm.unm.edu/index.html) is seeking...

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Assistant/Associate/Professor of Pediatrics (Neonatology)

Join the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria as a full-time Neonatologist.

Peoria, Illinois

University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria

Professor / Assistant Professor (Tenure Track) of Quantum Correlated Condensed and Synthetic Matter

The Department of Physics (www.phys.ethz.ch) at ETH Zurich invites applications for the above-mentioned position.

Zurich city

Associate or Senior Editor, Nature Communications (Structural Biology, Biochemistry, or Biophysics)

Job Title: Associate or Senior Editor, Nature Communications (Structural Biology, Biochemistry, or Biophysics) Locations: New York, Philadelphia, S...

New York City, New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Faculty (Open Rank) - Bioengineering and Immunoengineering

The Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) at the University of Chicago invites applications for multiple faculty positions (open rank) in ...

Chicago, Illinois

University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Global Ocean Sampling Expedition (GOS)

In 2004, after a successful pilot project of shotgun metagenomics sequencing at the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series site, J. Craig Venter, PhD, and a Venter Institute team launched the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) Expedition. Inspired by 19th Century sea voyages like Darwin's on the H.M.S. Beagle and Captain George Nares on the H.M.S. Challenger, The Sorcerer II circumnavigated the globe for more than two years, covering a staggering 32,000 nautical miles, visiting 23 different countries and island groups on four continents.

The Sorcerer II circumnavigated the globe for more than two years, covering a staggering 32,000 nautical miles, visiting 23 different countries and island groups on four continents.

Millions of new genes and nearly 1000 genomes for uncultivated lineages of microbes, as well as a more comprehensive understanding of marine microbiology through community datamining resulted from this historic project. Collaborative efforts and subsequent expeditions to the inland seas and lakes of Europe, Antarctica, and the Amazon River have greatly increased the known diversity of ecosystems and microbial diversity.

Global analyses of the results have provided insight into what environmental variables most dictate microbial diversity and function in a lineage-specific basis. Numerous new lineages of viruses for both bacteria and eukaryotes have been identified. The most recent expeditions, conducted in 2017, systematically examined the microbes that colonize plastic pollution in the marine environment. Collaborative analyses of both local and global aspects of the GOS expedition data are ongoing and open to new partners.

- Andrew Allen, PhD

- Christopher Dupont, PhD

- Robert M. Friedman, PhD

- J. Craig Venter, PhD

The Voyage of Sorcerer II

Read the captivating story of exploration and discovery that chronicles the Global Ocean Sampling Expedition.

Order your copy now.

2004-2006 Expedition

Collaborative agreements.

Data Sharing and Agreements from Past Voyages

Press Release

Slides (PDF)

Expedition Fact Sheet (PDF)

Permits Fact Sheet (PDF)

CAMERA Press Release

CAMERA Fact Sheet (PDF)

GOS Data at Genbank

Collaborators

The Census of Marine Life (COML)

COML Annual Report (PDF)

COML Annual Highlights (PDF)

Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Salk Press Release (PDF)

2009-2010 Expedition

Fact Sheet: Overview (PDF)

Fact Sheet: Previous Global Ocean Sampling Expeditions (PDF)

Related Research

- Environmental Sustainability

Past Voyages

Sorcerer ii circumnavigation 2004-2006.

In 2004, Dr. Venter and his team at JCVI launched the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) Expedition. Inspired by 19th Century sea voyages like Darwin's on the H.M.S. Beagle and Captain George Nares on the H.M.S. Challenger, The Sorcerer II circumnavigated the globe for more than two years, covering a staggering 32,000 nautical miles, visiting 23 different countries and island groups on four continents. Funding for this voyage of the Sorcerer II came from the J. Craig Venter Science Foundation (now JCVI), the U.S. Department of Energy , and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

After a successful pilot project in the Sargasso Sea in 2003, Dr. Venter and his Expedition team set out to evaluate the microbial diversity in the world's oceans using the tools and techniques developed to sequence the human and other genomes. With a better understanding of marine microbial biodiversity, scientists will be able to understand how ecosystems function and to discover new genes of ecological and evolutionary importance. The Sorcerer II Expedition finished its circumnavigation in 2006 and Venter Institute scientists and collaborators published the results from the first phase of the Expedition in PLoS Biology in March 2007.

This publication ushered in a new era in genomics. The GOS data represent the largest metagenomic dataset ever put into the public domain with more than 7.7 million sequences or 6.3 billion base pairs of DNA. The sheer size and complexity of this dataset has necessitated new tools and infrastructure to allow researchers worldwide access and analysis capabilities. The Community Cyberinfrastructure for Advanced Marine Microbial Ecology Research and Analysis ( CAMERA ) is an online database and high-speed computational resource developed with funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in a collaborative effort between UCSD's Division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) and JCVI. This first glimpse into the gene, protein and protein family world of microbes has shattered long held notions about evolution, function, and diversity.

Expedition 2007-2008

When the first third of the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling Expedition was published, Dr. Venter and his team realized (as stunning and extensive as these results were — six million new genes and thousands of new protein families) they had only scratched the surface of the microbial diversity in the oceans. The team decided to continue their journey but this time focusing on diverse and in some cases, extreme environments. From surface waters to deep sea thermal vents, high saline ponds and polar ice, JCVI scientists continued to add to the microbial "earth catalogue" in 2007 and 2008.

The Sorcerer II set sail in December 2006 from Virginia heading through the Chesapeake Bay, and then south along the East Coast of the United States. After a transit through the Panama Canal, the vessel headed north through Central American waters and on to Mexico sampling in the Sea of Cortez for an extensive time. The Expedition continued up the West Coast of the U.S. into Alaska. While in Alaska the Sorcerer II took samples in Glacier Bay National Park including water taken from melting glaciers there. After this Sorcerer headed south again to her home port of San Diego.

Throughout 2008, the Sorcerer II conducted extensive sampling in the waters off San Diego and the coast of California, Oregon and Washington. This was done to ensure that both coasts of the US had adequate samples taken. Much of this sampling was done onboard Sorcerer II but several excursions were conducted by JCVI scientists onboard other collaborators' vessels including those done with Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of Washington, Oregon Health and Science University, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, and the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations.

Several JCVI researchers also participated in deep sea sampling cruises as part of expeditions onboard the R/V Atlantis which carries the deep-sea submersible, Alvin. These expeditions were done in collaboration with scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of Delaware, and other institutions The JCVI scientists were interested in sampling the underwater geysers in the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Cortez to capture the viruses living in these extreme conditions.

JCVI scientists also conducted several sampling trips to Antarctica where they sampled via collaborator vessels along the route to Antarctica, and in several stratified lakes to understand the microbial diversity in these harsh polar conditions. These are the first metagenomic/metaproteomic studies conducted in such low temperature extremes.

The J. Robert Beyster and Life Technologies Foundation 2009-2010 Research Voyage of the Sorcerer II Expedition

Having successfully completed a global circumnavigation, conducted ongoing sampling in waters off California and the west coast of the United States, and carried out sampling with other collaborators in extreme conditions such as Antarctica and deep-sea ocean vents, the research vessel Sorcerer II and Dr. Venter embarked on the waters of Europe . This two-year leg of the Sorcerer II Expedition, funded by generous donations from the Beyster Family Foundation Fund of The San Diego Foundation and Life Technologies Foundation, explored the microbial life in the waters of the Baltic, Mediterranean, and Black Seas. These are scientifically important because they are among the world's largest seas isolated from the major oceans.

Sampling Route

The Sorcerer II left her home port of San Diego, California on March 19, 2009 heading south along the coast of Mexico, taking a 200 to 400 liters water sample approximately every 200 miles, filtered it through progressively smaller filters to capture the various sized organisms, and then freeze the filters with the captured microorganisms for shipment back to the JCVI labs in Rockville, MD or San Diego, CA where the sequencing and analysis is done. The team visited the following countries: England, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Estonia, and other Baltic countries, Spain, Italy, Germany, and Bulgaria.

Data Sharing

Scientific results from the Sorcerer II expedition have the potential to substantially advance the world's understanding of microbial communities, including the vital role that microorganisms play in the healthy functioning of natural ecosystems. For this reason, genomic sequencing data from the expedition will be publicly available to the international research and educational communities.

The genomic analysis of microbial communities may be particularly useful to the countries in which samples are taken. For example, these data may enhance a country's ability to monitor and protect its biodiversity. After these data are published, researchers in a given country may wish to pursue further study of microbes of particular scientific interest or potential commercial value.

The Venter Institute is a not-for-profit basic science research institute. Results from the microbial sampling and genomic sequencing research will be published in the scientific literature in collaboration with in-country scientists involved in the program. The data will be deposited in the publicly available GenBank or through a new web-based database established specifically for environmental genomics data. They will be publicly available to any scientist worldwide.

Consistent with national laws and applicable international treaties, and under the guidance of the U.S. Department of State, the Venter Institute obtains permits for research and sampling from every country in which samples will be taken. Scientific collaboration, education and training are an important part of the Sorcerer II Expedition as the vessel travels around the globe. In many countries, the Venter Institute has also signed memoranda of understanding describing additional components of the collaboration.

The Venter Institute develops cooperative relationships with leading international researchers located in each sampling region. All required research permits are obtained before sampling begins. In addition, the Venter Institute offers to develop memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with all countries where sampling takes place.

These memoranda typically include five fundamental principles of the Sorcerer II expedition:

- The purpose of the Expedition is to advance scientific knowledge of microbial biodiversity and humankind's basic understanding of oceanic biology, yielding insights into the complex interplay between groups of microorganisms that may affect environmental processes.

- Genomic sequence data from the study will be publicly available to scientists worldwide.

- No intellectual property rights will be sought by the Venter Institute on these genomic sequence data.

- The Venter Institute and its research collaborators will coauthor one (or more) scientific journal articles that describe and evaluate these genomic sequence data.

- The Venter Institute will offer training opportunities to scientists and students in the countries where sampling is conducted.

Biological Resources Access Agreement

Memorándum de Entendimiento para la Colaboración en Biodiversidad Microbiana [Español] | Signature Page

Memorandum of Understanding for a Collaboration on Microbial Biodiversity [English Translation]

French Polynesia

Convention Relative a la Mise En Oeuvre de la Campangne de Recherche — «Etude de la Biodiversite Microbienne dans la Region Pacifique Sud» Menee par M. Craig Venter [Français]

Agreement on Implementing the "Study of Microbial Biodiversity in the South Pacific Region" — Research Campaign Led By Mr. Craig Venter [English Translation]

Statement of Understanding

New Caledonia

Convention pour la Mise En Euvre de la Campagne de Recherche — «Etude de la Biodiversity Microbienne Dans le Pacifique Sud» Menee par L'instutte for Biological Energy Alternatives [Français]

Agreement for non Commercial Material Transfer And Carrying Out Research in the Seychelles

Material Transfer and Carrying Out Research in Zanzibar

Code of Ethics Agreement for Foreign Researchers Undertaking Researches within the Flora and Fauna of Vanuatu

Publications

Msystems. 2017-02-14; 2.1:, the baltic sea virome: diversity and transcriptional activity of dna and rna viruses, environmental microbiology. 2015-12-01; 17.12: 5100-8., closing the gaps on the viral photosystem-i psadcab gene organization, the isme journal. 2015-07-01; 9.7: 1648-61., connecting biodiversity and potential functional role in modern euxinic environments by microbial metagenomics, the isme journal. 2015-05-01; 9.5: 1076-92., genomes and gene expression across light and productivity gradients in eastern subtropical pacific microbial communities, proceedings of the national academy of sciences of the united states of america. 2015-01-27; 112.4: 1173-8., genomic and proteomic characterization of "candidatus nitrosopelagicus brevis": an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the open ocean, the isme journal. 2014-09-01; 8.9: 1892-903., picocyanobacteria containing a novel pigment gene cluster dominate the brackish water baltic sea, plos one. 2014-02-27; 9.2: e89549., functional tradeoffs underpin salinity-driven divergence in microbial community composition, current opinion in microbiology. 2013-10-01; 16.5: 605-17., lineage specific gene family enrichment at the microscale in marine systems, genome announcements. 2013-01-01; 1.1:, draft genome sequence of a single cell of sar86 clade subgroup iiia, the isme journal. 2012-07-01; 6.7: 1403-14., influence of nutrients and currents on the genomic composition of microbes across an upwelling mosaic, the isme journal. 2012-06-01; 6.6: 1186-99., genomic insights to sar86, an abundant and uncultivated marine bacterial lineage, plos one. 2012-01-01; 7.5: e42047., metagenomic exploration of viruses throughout the indian ocean, standards in genomic sciences. 2011-07-01; 4.3: 418-29., theviral metagenome annotation pipeline(vmgap):an automated tool for the functional annotation of viral metagenomic shotgun sequencing data, genome biology. 2011-06-27; 12.6: 117., genomes of uncultured eukaryotes: sorting facs from fiction, plos one. 2011-03-23; 6.3: e17722., single virus genomics: a new tool for virus discovery, plos one. 2011-03-18; 6.3: e18011., stalking the fourth domain in metagenomic data: searching for, discovering, and interpreting novel, deep branches in marker gene phylogenetic trees, applied and environmental microbiology. 2011-02-01; 77.4: 1512-5., novel antibacterial proteins from the microbial communities associated with the sponge cymbastela concentrica and the green alga ulva australis, nature. 2010-11-04; 468.7320: 60-6., genomic and functional adaptation in surface ocean planktonic prokaryotes, bioinformatics (oxford, england). 2010-10-15; 26.20: 2631-2., metarep: jcvi metagenomics reports--an open source tool for high-performance comparative metagenomics, proceedings of the national academy of sciences of the united states of america. 2010-09-14; 107.37: 16184-9., characterization of prochlorococcus clades from iron-depleted oceanic regions, proceedings of the national academy of sciences of the united states of america. 2010-08-17; 107.33: 14679-84., targeted metagenomics and ecology of globally important uncultured eukaryotic phytoplankton, bmc biology. 2010-05-25; 8.70., expansion of ribosomally produced natural products: a nitrile hydratase- and nif11-related precursor family, environmental microbiology. 2008-09-01; 10.9: 2200-10., it's all relative: ranking the diversity of aquatic bacterial communities, bmc bioinformatics. 2008-04-10; 9.182., gene identification and protein classification in microbial metagenomic sequence data via incremental clustering, plos one. 2008-01-23; 3.1: e1456., the sorcerer ii global ocean sampling expedition: metagenomic characterization of viruses within aquatic microbial samples, the isme journal. 2007-10-01; 1.6: 492-501., viral photosynthetic reaction center genes and transcripts in the marine environment, environmental microbiology. 2007-06-01; 9.6: 1464-75., assessing diversity and biogeography of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in surface waters of the atlantic and pacific oceans using the global ocean sampling expedition metagenomes, plos biology. 2007-03-13; 5.3: e85., untapped bounty: sampling the seas to survey microbial biodiversity, plos biology. 2007-03-01; 5.3: e17., structural and functional diversity of the microbial kinome, plos biology. 2007-03-01; 5.3: e16., the sorcerer ii global ocean sampling expedition: expanding the universe of protein families, plos biology. 2007-03-01; 5.3: e75., camera: a community resource for metagenomics, plos biology. 2007-03-01; 5.3: e77., the sorcerer ii global ocean sampling expedition: northwest atlantic through eastern tropical pacific, science (new york, n.y.). 2004-04-02; 304.5667: 66-74., environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the sargasso sea, in the news, advocacy in action: effective techniques for shaping science policy, what's happening, hispanic heritage month, recently published, the current progress of tandem chemical and biological plastic upcycling..

- TED Speaker

- TED Attendee

Craig Venter

Why you should listen.

Craig Venter, the man who led the private effort to sequence the human genome, is hard at work now on even more potentially world-changing projects.

First, there's his mission aboard the Sorcerer II , a 92-foot yacht , which, in 2006, finished its voyage around the globe to sample, catalouge and decode the genes of the ocean's unknown microorganisms. Quite a task, when you consider that there are tens of millions of microbes in a single drop of sea water. Then there's the J. Craig Venter Institute , a nonprofit dedicated to researching genomics and exploring its societal implications.

In 2005, Venter founded Synthetic Genomics , a private company with a provocative mission: to engineer new life forms . Its goal is to design, synthesize and assemble synthetic microorganisms that will produce alternative fuels, such as ethanol or hydrogen. He was on Time magzine's 2007 list of the 100 Most Influential People in the World.

In early 2008, scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute announced that they had manufactured the entire genome of a bacterium by painstakingly stitching together its chemical components. By sequencing a genome, scientists can begin to custom-design bootable organisms, creating biological robots that can produce from scratch chemicals humans can use, such as biofuel. And in 2010, they announced, they had created "synthetic life" -- DNA created digitally, inserted into a living bacterium, and remaining alive.

What others say

“Either he is one of this era's most electrifying scientists, or he's one of the most maddening.” — Washington Post

Craig Venter’s TED talks

Sampling the ocean's DNA

On the verge of creating synthetic life

Watch me unveil "synthetic life"

More news and ideas from craig venter, our tomorrow: hopeful/daring talks in session 1 of ted2016.

Tomorrow is a promising day: It’s full of possibility in a way yesterday isn’t, but so much more immediate than the nebulous future. TED2016 kicks off with a session called “Our Tomorrow,” a chance to hear from speakers with big ideas on where we’re headed, from a 10-year-old writer to a titan who creates much of the television you watch today. […]

Unveiling "synthetic life": Craig Venter on TED.com

At a press event in Washington, DC, Craig Venter and team make a historic announcement: they’ve created the first fully functioning, reproducing cell controlled by synthetic DNA. He explains how they did it and why the achievement marks the beginning of a new era for science. (Recorded at the Newseum, May 2010 in Washington, DC. […]

Algae: a genomic-driven solution for sustainable energy

Genomicist Craig Venter and his company Synthetic Genomics Incorporated (SGI) have entered into a $600m strategic alliance with Exxon Mobil to develop a next-generation biofuel from photosynthetic algae. Algae absorb carbon dioxide and sunlight in aqueous environments, producing an oil of similar molecular structure to contemporary petroleum products. Algal fuel can be refined, transported and […]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

John Craig Venter (born October 14, 1946) is an American scientist . He is known for leading one of the first draft sequences of the human genome [ 1 ] [ 2 ] and led the first team to transfect a cell with a synthetic chromosome.

Craig Venter, the geneticist turned entrepreneur, had arrived with the captain and crew of Sorcerer II, his 95-foot sailing yacht that doubled as a floating field laboratory. His mission:...

For biological scientist and lifelong sailor Dr. J. Craig Venter those passages provided a major inspiration for his extensive voyaging aboard his 95-foot sloop Sorcerer II.

He’s circling the globe in his luxury yacht the Sorcerer II on an expedition that updates the great scientific voyages of the 18th and 19th centuries, notably Charles Darwin’s journey...

SAN DIEGO— More than two decades after making history by being an integral part of the Human Genome Project celebration, J. Craig Venter, PhD still holds a few surprises up his sleeve.

Current owner J. Craig Venter, wealthy maverick geneticist. Sail the world's oceans in style — and revolutionize genomics! Three well-appointed cabins sleep up to eight.

Geneticist J. Craig Venter is best known for his role in sequencing the human genome and creating a ‘synthetic’ cell containing only genes that are necessary for life.

In 2004, after a successful pilot project of shotgun metagenomics sequencing at the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series site, J. Craig Venter, PhD, and a Venter Institute team launched the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) Expedition.

Craig Venter, the man who led the private effort to sequence the human genome, is hard at work now on even more potentially world-changing projects. First, there's his mission aboard the Sorcerer II , a 92-foot yacht , which, in 2006, finished its voyage around the globe to sample, catalouge and decode the genes of the ocean's unknown ...

Sorcerer II, a private yacht outfitted to collect and freeze microbial samples, netted a huge bounty of DNA sequence. CREDIT: J. CRAIG VENTER INSTITUTE After relishing the role of David to the Human Genome Project's Goliath, J. Craig Venter is now positioning himself as a Charles Darwin of the 21st century.